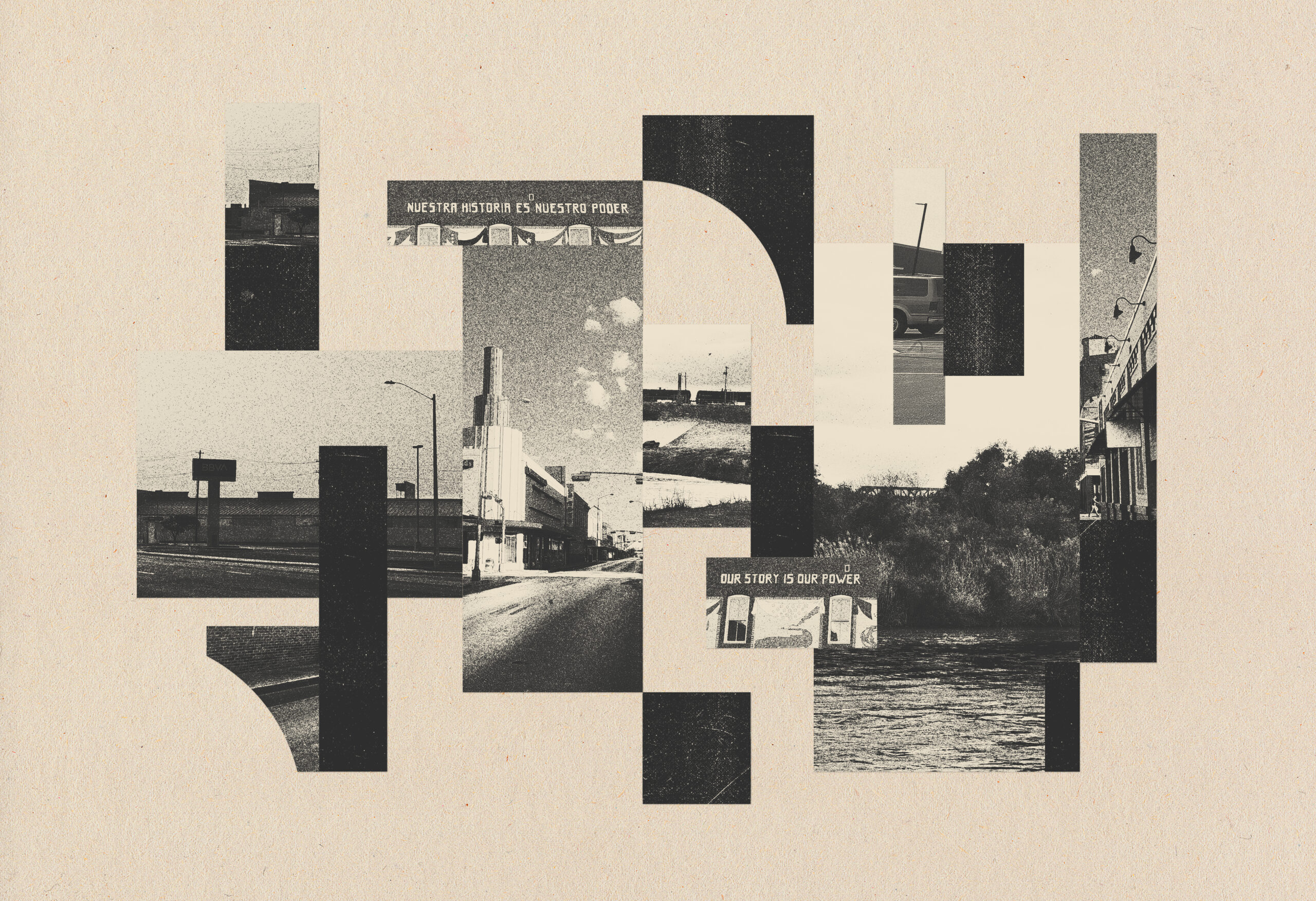

It is hard to tell where Laredo, Texas, ends and Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, begins. A quick tour of the area amounts to a crash course in the arbitrariness of borders. Laredo is one city, one people, with a militarized line of defense running through its center.

Adapted to the course of the Rio Grande, this vertical section of border has historically been relatively fluid. Workers, shoppers, and school children commute through the checkpoints on a daily basis. Streams of goods and money cross back and forth in trucks that rumble through the night. Couples and families communicate across national lines, which take on a variety of forms: a bridge, a river, a high fence, a low fence, a park, a mall. These are the ordinary interactions of one community — despite the drones flying overhead, the hundreds of armed border agents patrolling the lines, and the white noise of Fox News fear-mongering. Walking around Laredo or Nuevo Laredo, and talking to people on both sides — neither fully Mexican nor American, their very own thing — the enforced fiction of the border, of legals and illegals, stops making sense. Laredo gives you a good idea of what would have been lost to Trump’s wall — and indeed, what was lost when COVID-19 gave the former president a reason to shut down the border. The two cities grew farther apart overnight. Their shared identity, based on constant interaction, suddenly split. The checkpoints were shut down to limit inbound land border crossings to “essential travelers,” meaning U.S. citizens (who could cross both ways throughout the crisis), residents, and Mexicans traveling for accredited work, medical reasons, and educational purposes. The patrols stepped up. People lost their jobs. Couples and families were separated. Newly divided, the differences between life on the two sides of the border were suddenly exacerbated.

Those differences were always there, certainly. It starts with the quality of the roads. While Laredo has a web of megahighways and perfectly paved roads, the streets of Nuevo Laredo are dotted with potholes and cracked cement. The disparities in medical care are less visible but equally palpable. Residents of the American side of the border often cross over to buy medicine or go to the dentist, since both are cheaper there, while residents on the Mexican side visit the United States for high-end medical treatment if they can afford it. After the shutdown of March 2020, each side was locked in with their particular problems. A community accustomed to looking across the border for their support networks was forced to look to their own country for help. Families divided by the border faced similar plights, but with vastly different resources. One community was failed by two governments.

You’re On Your Own

The Mexican government’s mismanagement of COVID-19 may ring painfully familiar to American readers. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador kicked off pandemic season by downplaying the severity of the virus: This was just another coronavirus, he said. In the first months of the pandemic, López Obrador was seen still eating out at restaurants, and encouraged Mexicans to do their part in stimulating the service economy. In his daily press conferences, he dismissed the use of masks, and claimed that his good luck charm would protect him. At that point, Mexico was already a world leader in COVID deaths.

Like Trump, López Obrador valued appearances over impact, except that he did so in an even more medically underserved country. A neglectful testing regime allowed the government to actively undercount coronavirus casualties. Mexico’s death toll would have to be revised drastically upward several times starting early in the pandemic, in response to sustained pressure campaigns from t he media. (On June 30, 2021, for example, the official death count was 220,000 deaths, while health ministry data suggested the real number was likely closer to 350,000.)

López Obrador focused his national strategy on increasing hospital capacity, partially to obfuscate decades of neglect and underfunding of the health sector. Authorities urged people to stay home to avoid overburdening the hospitals. They put a traditional spin on this: Instead of saying ‘You’re on your own,’ they instead said, ‘You have your family.’ “This public health crisis won’t be resolved in our hospitals, it will be resolved in our homes,” the president declared on March 26, 2020. “We have a fundamental institution: the Mexican family…our main social security institution. Now they are helping us take care of the most vulnerable population, our older adults, those with diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, and pregnant mothers.” Finally, he said, “we have millions of nurses in our homes,” meaning women. The family was to be the center of Mexico’s response; instead, it turned out to be one of the epicenters of the crisis.

A Family Tragedy

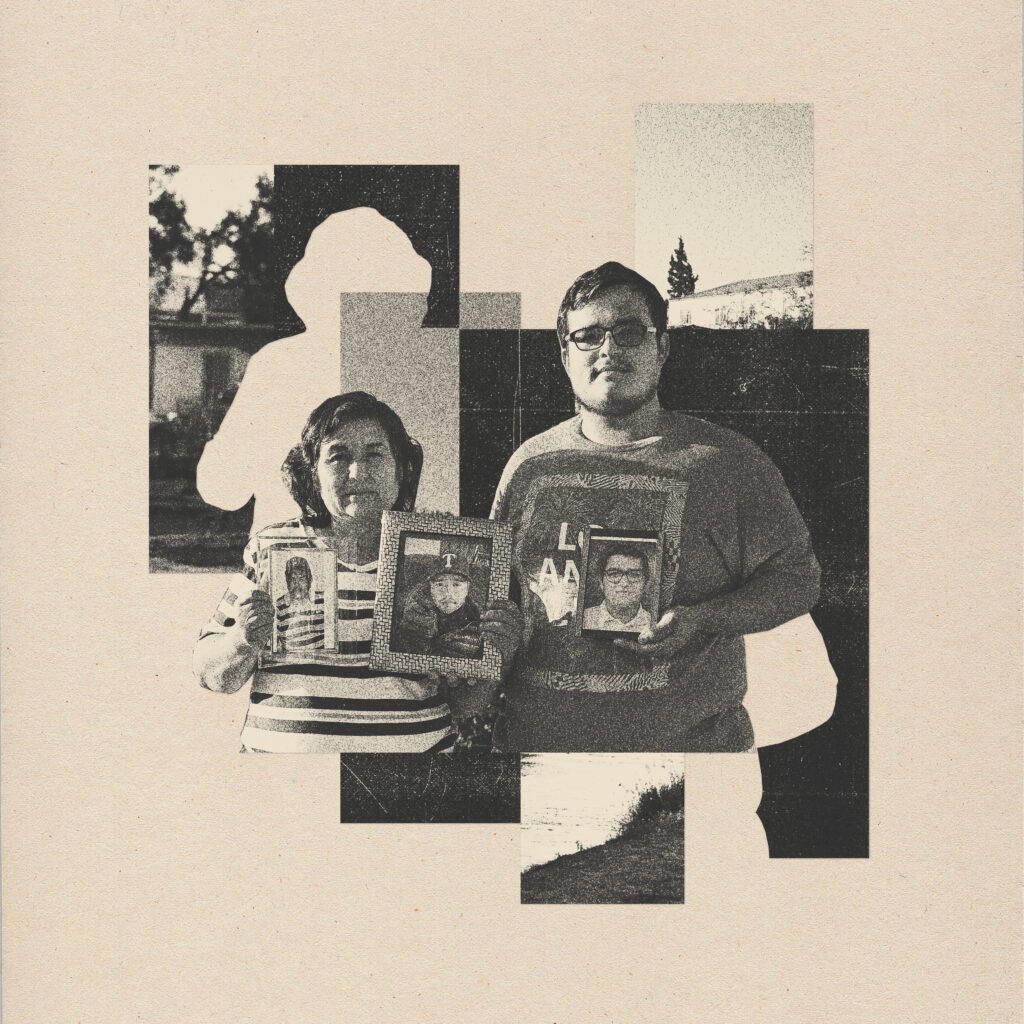

Juan Raymundo Arreazola was one of the first people to get COVID-19 in Nuevo Laredo. A trained nurse, he knew what to do. Instead of seeking care from his family, he immediately sent his wife and baby away and isolated himself at home. He tried his best to treat his symptoms, but his health declined rapidly. A week in, he called an ambulance. He sent his family regular letters from the hospital, but one day they suddenly stopped. On May 9, at the age of 31, Juan Raymundo became one of the first people in the city to die of the coronavirus. When his father, Juan Raymundo Senior, answered the phone at 10 p.m. that night and heard the news, he fainted.

His mother Rosalinda Arrezola set up an altar for her oldest son on the sidewalk, as funerals were banned. Many in the community came out to show their support, though some crossed the street for fear of catching the virus. In the aftermath of this tragedy, Rosalinda and her youngest son, Orlando, stopped going to work, but her husband, a 57-year-old employee at a customs agency, refused to abandon his post. It didn’t take long for Orlando and his father to both contract COVID-19.

If he had survived, Juan Raymundo Junior may have counseled his mother against nursing her husband and son at home. In his absence, Rosalinda spent those weeks pacing from bed to bed, checking fevers and administering medication. Her middle son Pablo, a seminarian, came to help her, but there was little either of them could do. Rosalinda’s husband died at home in her arms. “My husband never accepted the death of my first son, and I know the sadness he felt was what took him away from us,” she says.

Soon after Orlando was admitted to the local ICU, Pablo also fell sick and joined him there. And while Orlando slowly improved, Pablo rapidly declined. He begged his mother to bring him home, but four days later, he passed away at the age of 28. Rosalinda doesn’t know how she has managed to endure the nightmare. Only one detail gives her solace. “I thank God my husband never learned about the death of his second son.”

The Arreazolas’ tragedy is a microcosm of what happened all over Mexico: the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives; an outline of the growing holes in Mexico’s social safety net. Health care workers bore the brunt of this tragedy; at the time of writing, no other nation on record has lost more of them. The epicenter of Mexico’s COVID-19 crisis is populous, low-income neighborhoods, full of multigenerational households like the Arreazolas. Most of these live in big cities, so smaller cities like Nuevo Laredo received far fewer resources. Hospitals were short on ICU beds, medicines, and most importantly, adequate doctors. Many people monitored their health at home with oximeters. Some acquired oxygen tanks on the black market. Others turned to home remedies like teas, or more dubious substances, such as unproven supplements and chlorine. Only the sickest patients were admitted into hospitals. Combined with a prevalence of underlying conditions, this ensured that Mexico would long have one of the highest death rates for intubated patients in the world.

A Community Rises Up

Roberto Garcia, a 33-year-old cardiologist from Nuevo Laredo, saw it coming. When the first cases registered in Mexico in early 2020, Garcia reached out to Nuevo Laredo’s health officials, urging them to take precautionary measures. He visited local hospitals and found they lacked contingency plans and basic equipment like ICU beds, ventilators, and protective supplies. Within a few months, the city’s hospitals were overwhelmed, and masses of doctors began dying from COVID-19.

It was clear to Garcia that a community response was needed. In the absence of effective leadership by political and public health officials, the people had to rise up to help each other. Garcia began keeping track of health care worker deaths on a Facebook page, long before the federal government acknowledged it as a crisis. His Facebook group soon had thousands of members, eager for reliable information that was not reaching them through official channels. When hospitals ran out of capacity, the group filled with posts about oxygen tank rentals. When COVID-19 tests were hard to find, users shared testing site locations.

This everyday heroism proved infectious. It absorbed Lourdes de Leon, a 37-year-old event planner and particularly active member of Garcia’s Facebook community. With no parties to plan, she instead focused all her energy on mutual aid. Leon, who already supported the most vulnerable around her — regularly providing meals to an elderly neighbor — expanded her operation. Her living room is full of ripe fruits and vegetables that others donated to her food drives. “There’s so much need in Nuevo Laredo,” the mother of two says. She found ways to stretch every peso donated, creating masks from a borrowed sewing machine and face shields from Coca-Cola bottles. In dire times, these small interpersonal interventions make the difference between life and death.

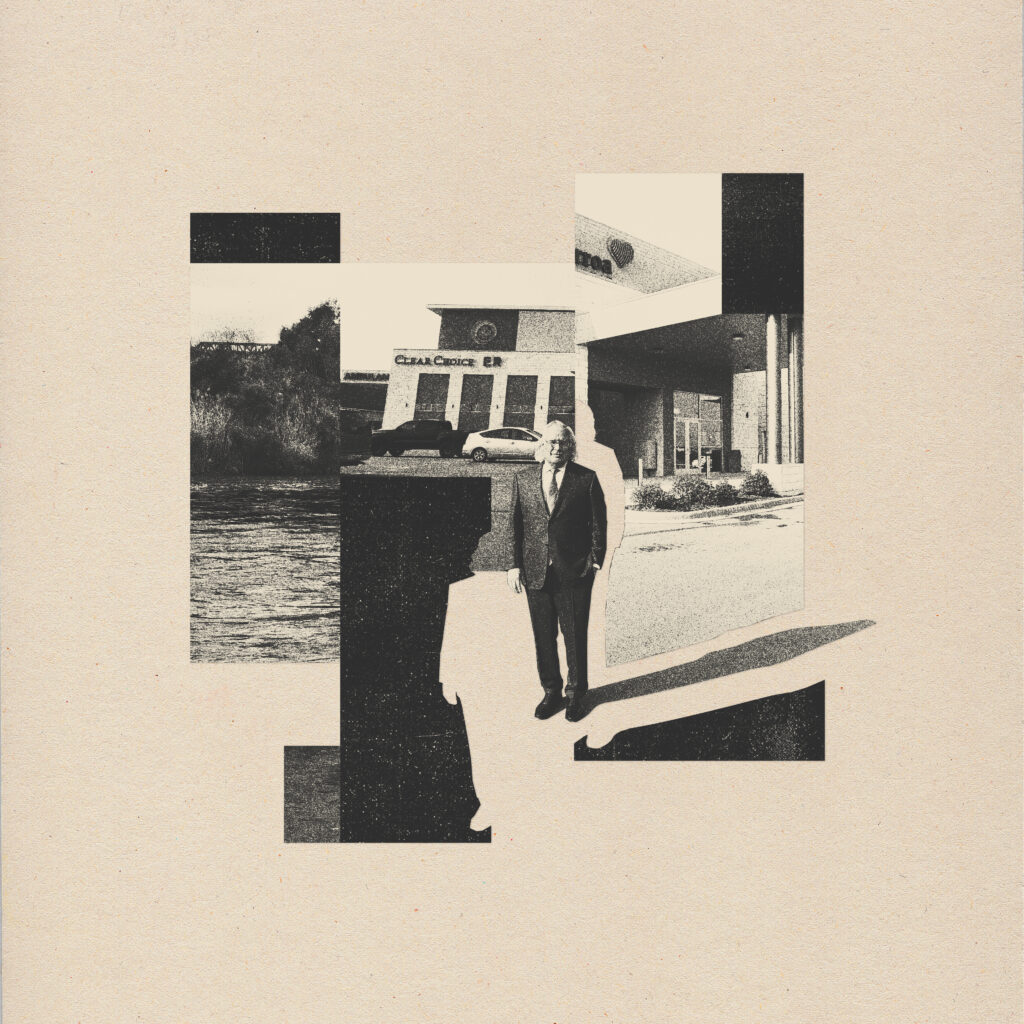

Across the Rio Grande, Dr. Victor Treviño, Laredo’s Health Authority, is busy dealing with the other side of the crisis. Treviño gives weekly media briefings from his office, which he has fashioned into a makeshift studio with big camera lights. Standing in front of a virtual backdrop of a spotless hospital room to hide the messy stacks of papers behind him, and wearing his trademark thick, large glasses, the 73-year-old family doctor chooses a sober but forceful tone to convey the gravity of the unfolding crisis: scarce ICU beds and health care workers, mounting infections among children attending recently reopened schools. He tries not to create panic but doesn’t sugarcoat the facts, either. In May, the city is considering the creation of a pediatric overflow holding area in preparation for a new breakout. “If we get to that point,” he says. “God help us.”

Like its sister city, Laredo was unprepared for a pandemic. On the American side, at least, city officials acted quickly. On March 15, 2020, the city declared a Public Health Emergency. It set the most restrictive policies in the state, shutting down non-essential businesses like restaurants, bars, malls, and gyms. The city council enacted the country’s first mandatory mask policy. Yet cases still surged, due to a shortage of protective equipment, testing shortages, and Laredo’s proximity to Mexico. The inherent mobility of the city heightened the already ubiquitous threat of transmission. Truck drivers involved in international trade pass through Laredo after crossing both countries. Residents of both cities continued to cross the border — to use the common parlance, legally and illegally. Nuevo Laredo’s lack of testing was becoming a problem for both cities.

Treviño, who can trace his roots in Laredo back to its “founding” 200 years ago, has always prided himself on eschewing politics. But in this crisis, he found himself demanding that Texas Governor Greg Abbott finally stand up for his city’s public health interests. Treviño pushed the city council to impose a curfew limiting movement from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., and ordered hospitals to supply personal protective equipment to health care workers. He quarantined two privately operated detention centers used by the U.S. Marshals and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, much to the displeasure of then-attorney general William Barr. In August of 2020, when Texas A&M International University experienced a surge of COVID-19 cases, Treviño issued a quarantine order for students and employees of the university, but it was quickly overturned by the state. He has made himself a lot of enemies in the past year.

Despite the prompt measures taken by him and his colleagues, Laredo became one of the worst-hit cities in the U.S. Compared to other cities in Texas, they were drastically underserved. In the two local hospitals (which serve a population of over 260,000), patients were being treated in hallways due to a lack of space. Others waited in long lines for the speculative coronavirus treatment remdesivir. By winter, Laredo had the highest number of positive cases and hospitalizations per capita in the state. Nevertheless, the city kept reopening.

Ricardo Cigarroa, a prominent cardiologist in the community, often referred to as “the Dr. Fauci of South Texas,” doesn’t pull any punches when attributing the death toll to the lack of leadership. “To our city government, to our state officials, to our governor, you are failing us,” he said in a Facebook Live video in late January. Laredo’s surge reached its peak in January. In those days, Cigarroa was signing 4–5 death certificates per day. The influx of medical supplies to the city was unreliable and slow. Cigarroa had a mounting sense that this majority Latino city was, to state officials, just an afterthought.

Vaccine Inequality

Cigarroa’s impression hardened into conviction during Laredo’s slow vaccine rollout. He started publicly questioning whether racial animus factored into the decision by Republican state legislators to allocate far more vaccine doses to nearby Lubbock County, which has roughly the same population but is proportionately less Latino. “Is it back to [the days of] MALDEF and discrimination?” he asked in The New York Times, citing the history of medical racism in Texas that ultimately led to the formation of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund in the 1960s. State officials insisted that the vaccines allotted to Laredo were based on the number of health care workers in the city. Smaller or equally sized counties with a larger presence of health care workers received five times as many vaccines. In short, Laredo was doubly punished for being medically underserved.

Facing immense pushback, the state increased the number of shots allotted to the city in mid-March 2021. At this point, vaccines are widely available without appointment in Laredo’s malls, supermarkets, pharmacies, and schools. In fact, the city has one of the highest vaccination rates in Texas, with 60 percent of eligible residents receiving their shots. From El Paso to Brownsville, counties along the border exceeds the state average for vaccinations.

By contrast, Mexico’s vaccine rollout has been slow and spotty. As of late August 2021, almost 30 percent of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to over 50 percent of the U.S. population. The Mexican government has acquired a wide array of vaccines, including those developed by Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Sinovac, AstraZeneca, as well as Sputnik V. Mexicans are assigned a shot from a particular manufacturer; they do not get to choose which one. The country is now vaccinating people 18 and older, yet the number of positive cases continues to rise. Hospitals are saturated in some states. Schools in Nuevo Laredo reopened on August 30, 2021, amid high uncertainty brought by a third wave of cases of the alpha, gamma, and delta variants.

The rollout within Mexico has also been unequal. The impoverished southern states of Chiapas and Oaxaca have inoculated less than 50 percent of their population, while the northern states that border the U.S. like Baja California and Tamaulipas have reached over 70 percent [as of August 2021]. Frontline health care workers were the first to get vaccinated according to the national plan in late December 2020. Private sector health workers (who, in Mexico’s patchwork health care system, provide care across social classes) were not included. This sparked outrage among doctors and nurses, and a wider conversation about vaccine equity. On April 19, 2021, health care workers in Nuevo Laredo from both private and public sectors held a peaceful protest to demand their shot. At the time of writing, Nuevo Laredo has yet to offer vaccination to all its health care workers, while Laredo, Texas, is trying its best to win over vaccine skeptics.

While the land border remains closed, you can now fly to Mexico. A class selection process ensues: Wealthy Mexicans have been taking daytrips to cities like Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio to get their COVID-19 shots, or even to border towns like McAllen and Laredo. Most residents of Nuevo Laredo can’t afford flights to access the vaccine, despite living just a few miles from American soil.

The U.S. has a vested interest in accelerating Mexico’s vaccine rollout. In late March, the country loaned 2.7 million AstraZeneca doses to Mexico, as the jab has not yet gained an emergency use authorization from the FDA. This display of diplomacy, while generous, exemplifies the asymmetric relationship between rich and middle to low-income countries in the global race to contain the virus. Some countries have enough to give away or use as booster shots, while others are scrambling to get enough first shots to cover their most vulnerable populations.

The U.S. could amass up to 1 billion surplus vaccines by the end of 2021, and President Joe Biden has already pledged to share 80 million doses globally, but many more are needed. In July, the head of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, called out the “shocking imbalance” of global vaccine distribution and “moral failure” of vaccine inequity. As of July 2021, of the more than 3.5 billion doses distributed globally, over 75 percent have gone to only 10 countries.

To spur reopening, the U.S. donated 1.35 million doses of Johnson & Johnson shots to 39 border towns in June 2021, from Tijuana out west all the way to Reynosa. The two countries have been in talks about reopening the border, but the date for doing so keeps being pushed back.

The decision is a political issue as much as a public health one. Biden’s win rekindled hope for migrants and asylum seekers in limbo on the border. The new president ended the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” policy upon taking office, which was implemented in 2019 and had forced 71,000 people to await their asylum process in Mexico under precarious and dangerous conditions. The program will likely be reinstated soon. Amid a rising number of people reaching the U.S. southern border and a lawsuit filed by Texas and Missouri against Biden’s administration for ending the policy, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered it to be reimplemented in late August. America’s message to other migrants remains clear: “Do not come.”

Laredo was doubly punished for being medically underserved.

Biden has so far continued most of his predecessor’s immigration policies. Trump officials arguably did some of their most prolific work legally enshrining their hardline views on immigration. To the frustration of immigration activists, the new administration has offered much hopeful rhetoric and little substantive legal action on this front. The Biden administration has continued Trump’s Title 42, a policy implemented on March 20, 2020, that allowed U.S. border officials to immediately expel hundreds of thousands of migrant adults and children without due process or hope of asylum. The deported are now waiting for the border to reopen and their cases to be heard inside shelters in Mexican border towns like Nuevo Laredo, where they have limited access to tests and no COVID-19 vaccines. America continues to deport people en masse, many of them untested for the virus, adding to Mexico’s tragedy.

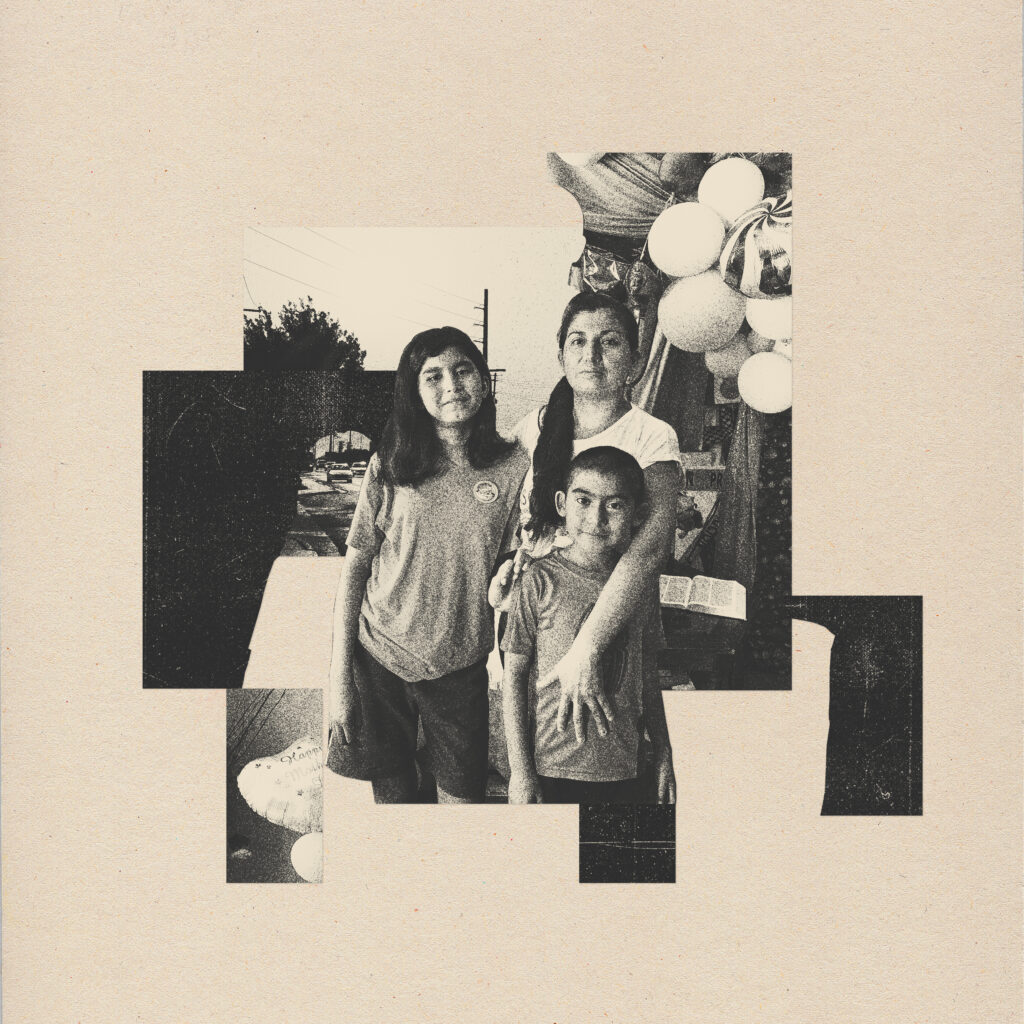

Ironically, this crisis has brought into sharp relief how interconnected our two countries are. Though this fact was seldom mentioned in media coverage, a disproportionate percentage of America’s celebrated essential workers are migrants from Mexico and other countries in Central America. These farmers, restaurant workers, delivery workers, factory workers, and nurses helped keep the U.S. afloat during this crisis. At the same time, they kept their families in Mexico alive when the government offered no relief to a population living under the strain of a hemorrhaging economy. In February 2021, remittances sent home to Mexico totaled $3.174 billion, the highest amount ever since records began in 1995.

These increased assistance efforts have come at a tremendous cost for migrants who have been more exposed to the virus and have less access to health services. Working dangerous jobs, living in ever-closer quarters due to gentrification, many of these people paid with their lives. After years of serving America, thousands of them made their final trip over the border this past year, returning to their country of birth in urns. When people use the word “illegals,” these are some of the people they are talking about.

The Deported

It’s late spring and the streets of quaint downtown Laredo, Texas, are still eerily empty. Local businesses here have suffered in the absence of customers visiting from Mexico.

Months-old products collect dust in shuttered stores, giving it a nostalgic impression of a place frozen in time. Rebecca Solloa works here, as the executive director of a Catholic shelter, and returns home to Nuevo Laredo every night to her new husband Hector Sol. Hector cannot cross the border.

The couple’s story begins over 30 years ago in San Antonio, Texas, where they dated on and off, only to fall out of touch. In 2019, after decades of estrangement, Rebecca, still living in America, had a premonition that Hector needed her help, and got in touch with him. It turned out that Hector, now 66 years old, had been deported back to Nuevo Laredo after spending three years in a federal prison for unlawfully reentering the United States. The two kept talking after that first call and soon decided they wanted to be together. They planned to get married in Nuevo Laredo.

The pandemic derailed their plans. Hector was living alone, with very little work, money, or support. He suffered through a bad case of COVID-19 without health insurance. Generally, life in Mexico had been hard on him. He had spent his whole life on the other side; it’s all he knew.

Marrying Rebecca earlier this year offered some relief. She now lives with him in Nuevo Laredo, but his homesickness for America remains. Every time Hector was deported in the past, he risked his life to make it back. That doesn’t seem in the cards anymore. Driving along the Rio Grande that separates him from Rebecca on a hot day in mid-May, he says, “If I cross, I’ll end up back in jail for being too stubborn.” He has few family members and friends left in Nuevo Laredo. All of his people are on the other side: his children, grandson, brothers, sisters, uncles, nieces, and nephews. He can’t even go for a walk with his wife on the fancier side of the wall.

Rebecca only spends half of her day in America, but that time comes with particular privileges. She was fully vaccinated by mid-March. Hector, meanwhile, had to wait months longer for his first shot of the Chinese Sinovac vaccine. His legal status is a strain on the relationship, Rebecca explains over the phone while sitting next to him in their home in Nuevo Laredo. But she refuses to give up. “I am going to continue to fight for him and look at all legal avenues so that he can come back to the U.S.” The fact that Hector is married to an American citizen could possibly help him down the line. It won’t be easy, but life on this side of the border rarely is.

“We have a long hard road ahead of us,” Rebecca says. She is getting ready to cross the bridge to her job in Laredo. Her husband escorts her halfway, going as far as he can go, and then turns back, awaiting her return.

From GROW’s Equity Issue, published in October, 2021. Original photographs throughout courtesy of Lorena Ríos.